Colin Spacetwinks is a writer of fiction, non-fiction, and criticism, but still probably most known for posting a bunch of shit online. They publish a bunch of their original work over on their itch.io page ranging from things like a collection of their personal tips and tricks to living and working with ADHD to a body horror story about coming to work on your day off. They also wrote that article about Christian Sonic the Hedgehog fandom that Alex shouted out on one of his drumming streams. Thanks, Alex.

What can I say that hasn’t been said? It has been a long, needlessly cruel year, and we the crisis we’re living in isn’t even over yet as I type this. I feel like a character in an unfilmed Paul Verhoeven script, writing about which video games I liked best this year while an ungodly amount of people died this year due to the cruelty and apathy of people in power across the board. While I don’t have the power and influence to be in the place of Nero fiddling while Rome burned, I do find myself feeling an awful lot like Roast Beef Kazenakis from the Achewood strip for September 2nd, 2004.

But something I keep in mind is that while comedy, and art, and yes, games, is not enough--it is still necessary. I cannot defeat a crisis by making jokes about it, and one shouldn’t make the common mistake of thinking truly cutting art can undermine the power of empires and the inertia of state cruelty. All this is true.

While all these will not resolve our problems, we still need them. For relief. For catharsis. For the spirit as much as anything else. I make jokes throughout this year to keep myself going and to help others do the same. It won’t turn the world around the way I want, but it helps lighten the weight.

To be there for each other as people means being there for each other with things that don’t seem as ‘important’, too. To help give each other that mental, spiritual, internal relief so the aches of the world don’t build up so high on us that we can’t possibly climb out from underneath them. I know I’m not the only one who turned to Giant Bomb every now and again this year for that kind of personal relief, to make it easier to smile and refresh the self, keep going, get some energy back to fight for a better world.

So making these lists, writing and talking about the games we loved this year, we shouldn’t get it twisted and think we’re making a massive, material impact.

But we shouldn’t think we aren’t doing anything, either. Even passively, we’re giving each other comfort. Support. Relief and catharsis, as I said.

Excuse my sappiness here for a moment, and let me say: May we continue to give each other that support, that relief, through 2021 and beyond.

Here’s to you, here’s to us, here’s to being there for each other.

11. Umineko When They Cry

In the category of “Best game I played this year and didn’t come anywhere close to finishing”, Umineko comes out at the top. It’s honestly comical at this point how many times I’ve said I want to get back to it and then don’t end up doing so for no end of reasons, some of them out of my control, some of them entirely within it, but I truly do want to get back to Umineko. There are so many wrapped together layers to this murder mystery, so many tangents of themes that all get wrapped back into one tight knit--covering everything from the cycles of abuse to the nature of what is “real” and what is not, of what fiction and imagination mean to us and how it impacts our material reality or how we perceive it, and none of it feels incidental or unnecessary. I’ve only played about a third of the Question arc, and the Question arc is just one half of the game, so there’s still tons for me to cover and find out! Who knows, it might end up back on my 2021 GOTY list too, and further enable my odd hobby of photoshopping old TV title cards to be about the game while I live-tweeted my thoughts on it!

Having played so little, I can’t--or perhaps just don’t want--to go that in depth with it, but it really is a marvelously thoughtful and tense story so far!

10. Road Trip Adventure

Actual driving makes me nervous. Can’t stand it. Put me in the driver seat of a car and my anxiety ramps up like wild. I can’t get a good feel for how much space in the universe I take up, how far away I am from anybody else and how likely I might be to crash into them. Too much to pay attention to in a steel carapace that’s all going at 60 miles-per-hour or more. Not that holding the car in place is any better--I vividly remember when I was learning to drive back in my teens with a stick shift, stalling out on a hill with about three cars behind me, panic climbing inside of my throat at an alarming rate, making it that much harder to focus and get the car back into gear and moving out of the way.

But when I’m not in the driver’s seat, or at least when I’m in a digital driver’s seat, I can find driving so soothing.

One of my favorite things to watch on Giant Bomb has been Alex’s trucking streams, and he himself has talked before about the soothing, almost meditative experience he can get from driving, both in the Truck Simulator games and in real life, going down long stretches of empty California highway and then back again. While I’ll never get the same comfort he does from actually having a wheel in my hands and my foot on a gas pedal, I also find myself relaxed just watching those long hauls, seeing the world go by, listening to some music. Even when the radio is tuned to European death metal pouring through the speakers and into my headphones, I still find myself with a steady heartbeat and a relaxed breath, adrenaline kept firmly in their reserved pockets.

In the last month of 2020, Road Trip Adventure delivered that same easygoing feeling. And it was badly needed after, well. I hardly need to say it, do I?

There’s this absurdity to Road Trip Adventure that ends up making itself even more relaxing to me. First is the cars themselves, which are little toys, penny racers, specifically the Choro-Q line of toy cars, a Japanese brand that’s been going for over 40 years now, with dozens of video game adaptations. They’re these squat, cute little things, and they talk, though not so like the cars from the Pixar movie. No mouths, no eyes, no limbs, no twisting and turning of their machinery to imitate human affectations. Just toy cars, talking, running businesses, and apparently even eating food and having systems of government--the very premise of Road Trip Adventure being that the President Car is tired of being president and is saying anyone who can beat him in a race gets to be president now--and never a wink or nod to the idea that this might be absurd. Fittingly, it’s a bit like being a child playing pretend again, dropping Hot Wheels into a city built out of Legos, making them have an entire active society, and not caring one whit how it would have to “actually” work to accommodate their steel frames. There’s coffee shops in your neighborhood, so the cars have coffee shops too. Why not? You’re here to enjoy yourself, not to think about the hows and whys, the lore for a world of living cars.

There’s two areas in Road Trip Adventure that make the biggest impression on my mind, that I can think of and just feel myself relaxing by calling them to my memory. And they’re right next to each other. The first is the long road taking you away from the starting city Peach Town. The second is the ocean itself.

The game has a day/night cycle, and taking that long road out of town during the bright hours of the day gave this relaxing atmosphere, emphasized and enhanced by instrumental music by Michael Walthius. The world layout and the simple, flat colors of the grass and sky around me made me feel like I was touring through the environments of a budget Christian video game. There wasn’t a soul around me, the world strangely empty, yet not feeling desolate, lifeless. It was more dreamlike. As if I had fallen asleep and my consciousness dropped out of my body and into a toy car, and that toy car had been dropped into a world where it was the only living thing that existed, and that was fine. Seeing row after row windmills as I crested hills brought a quiet smile to my face. I had no idea where I was going, nor what I would do once I got there. I didn’t know if there was anyone else around me or anything to do. In that moment, there was just me, the road, and the windmills. And that was fine. Great, even.

Then I pulled off-road and drove straight into the ocean. The game didn’t stop me. Didn’t pull me out, telling me “no, no, of course you can’t go in there, what are you thinking”. I just kept driving, surrounded by an endless blue, indestructible tires rolling over the very bottom of the ocean floor. Still nobody and nothing in sight. Not another car, not a fish, not anything. Me, the ocean, and the music. I had even less idea of where I was going or where I could go now.

chilling pic.twitter.com/sPGk2xp8Ut

— Colin Spacetwinks (@spacetwinks) December 16, 2020

And I kept driving without purpose, with Michael Walthius’ music on the radio to keep me company.

How relaxing. How wonderful.

9. Gravity Rush 2

Gravity Rush 2 hates the rich.

It really, really fucking hates the rich.

It’s an incredibly fun game, with mechanics that feel like someone looked at Spider-Man 2 The Movie The Game for the PS2 and went “I like this, but moving around the city could be way funnier”, switching out swinging for reversing and accelerating gravity, going from location to location less by flying and more by treating yourself as a ragdoll to be launched from one spot to another, smashing your body into the ground in a way that feels like you gave Johnny Knoxville superpowers. Though a Sony title, and written and directed by Keiichiro Toyama of Silent Hill 1 fame, it most reminds me of the movement from Sega games like Super Monkey Ball, Sonic Adventure 2, and NiGHTS Into Dreams, all fused together into one well flowing package. I have a blast playing it!

But what I think about the most is how much it hates the rich.

There’s a sequence in the game where you have to hop from one mansion to the next, using your control over the very force of gravity to take care of chores and tasks for obscenely wealthy people who can’t be bothered to do a thing for themselves. They think you’re their servant, because they think just about anybody but those obviously of their own class are their servants, and they order you around to use those superpowers of yours to water their plants as well as--in the part that reminded me the most of Spider-Man 2--retrieve a balloon for a child. A spoiled one who, like their parent, shows zero appreciation for what you’ve done, and even insults you for being poor. The final part of this chapter of the game has one of those rich people musing about how bored they are and respond with no limit of glee when a military officer tells them that they’re going to be ‘clearing out’ the islands and homes of the underclass, as well as the people who live there… so an amusement park can be built down there.

It might seem over the top at first glance--it certainly would’ve felt that way to me a decade or so ago--but now I think about all the places out there that have been, and are still aggressively, ruthlessly turned into tourism spots, using money, manipulated legal systems, and outright violent force in order to create ‘paradises’ for the well to do. All at the expense of everybody else. So they won’t be bored. So they can have somewhere nice to spend a couple weeks in the summer.

The gameplay of Gravity Rush 2 is very satisfying, you know? Has a great tactile feel to it. Especially when you’re hurling boxes at a hundred miles per hour at army goons carrying out the bored, petty whims of the elite.

8. Dark Souls

Yes, I’m extremely late to this party.

You have most likely already read thousands upon thousands of words about Dark Souls. And as much as I’m known for, and even feel comfortable, being extremely longwinded with my thoughts on games, you don’t need me to do the same here. So much has already been covered and mined out of this game, in critical responses and in games taking inspiration from it since.

But I still want to say something about it, so I want to cover a piece of it, a person in it, who doesn’t get the same kind of focus and theorizing and critical thought as others.

I want to say: Siegmeyer is my friend.

It’s not totally fair to say Siegmeyer doesn’t get all that much coverage, it’s just that it’s mostly treating him as something of a joke, and I’m not innocent here either. There’s a Mr. Bean aspect to him, where he’s bumbling through this incredibly dangerous world and you’re left at a loss as to how or even frequently ‘why’. You know why you’re here, what you’re here to do, even if the nitty gritty details of your quest are obfuscated, sometimes intentionally so. Siegmeyer wants adventure, and that’s it. The joy of the journey itself, in a place where death is at every corner.

He’s not the grizzled badass you’d expect for that desire, and that’s the point, to me. Solaire is the one who tends to get more of the focus when looking at Dark Souls from this angle, but Siegmeyer is just as important to me. He’s someone who feels like he shouldn’t be here, shouldn’t be surviving as long as he does, someone who seems out of place. And yet he goes on, without losing his cheer and breezy attitude about it all. Someone put it to me this way on twitter, and I find myself agreeing: Siegmeyer tries his best, and his best is pretty damn good, all things considered.

At the start of the game I was baffled by him, but the longer I spent, the more I was fond of him. He’s like a friend you know who has all these bizarre, incredible anecdotes, and you know he’s not making them up because he’s not telling you them to brag. Somehow he keeps falling into and out of these wild experiences and you can’t help but smile as he tells you these stories. It feels so good to come across Siegmeyer, to talk to him, to wonder how he got to where he did, and what’s on his mind now.

Siegmeyer is a friend, and a friend I wish you got to spend more time with. But I guess that’s one of the things that makes Dark Souls so good. Getting you attached to the onion knight and making you feel something lost when you can’t spend any more time with them, like a friend moving away.

What a kind soul, Siegmeyer is. I’d think of his laugh or his “Hmm hmm hmm” sometimes, and smile.

7. Valkyrie Profile: Covenant of the Plume

I loved the original Valkyrie Profile all the way back when it came out, but there’s no getting around the fact that it’s one of the most egregious examples of a game built to sell strategy guides. You want the true ending for that Norse mythology JRPG? Well pony up 15-20 bucks to Prima because good fucking luck figuring out how to achieve it on its own. Seriously, if you don’t already know the intricate and obtuse bullshit about Valkyrie Profile’s endings, I honestly recommend you look it up. An utterly bizarre chain of events that you have to do just right, the kind of “How the hell was I supposed to know that?!” that you could put around the same area of Simon’s Quest or various Sierra adventure game puzzles.

Covenant of the Plume doesn’t have this problem. All told, I’d actually say the DS tactics RPG is a better game, and a better story. It’s more focused, more balanced. The thing that sticks out to me the most about it is how it tackles the act of killing other characters, of sacrificing your own allies--and does it so well. Many other games going at this problem are… honestly kind of hollow. There’s either no real stakes at all, where choosing whether to kill someone or not just affects a few points on a skill tree or a mission reward (and so often the rewards for killing someone are so overwhelmingly better than the meager rewards or story quality of doing the right thing that it’s no wonder so many players choose the bloodier path, see Knights of the Old Republic and Force Lightning), or it’s worn out metacommentary, the game scolding and mocking you for enjoying being the bad guy, even as every system is built for you to enjoy it all, or gives you no choice but to kill. It wears thin.

With Covenant of the Plume, sacrificing your own teammates is a key game mechanic and story feature, and it makes both of them work by tying them tightly into the game’s difficulty. Sacrificing a teammate gives your main character a massive stat boost during a battle, and also gives them an unlocked skill afterwards. Around the beginning of the game you might think “Well, then I just won’t sacrifice anyone at all. What’s the problem?”

Then the difficulty starts ratcheting up.

Covenant of the Plume doesn’t say you have no choice but to sacrifice your allies for your own goals, but that it’s just not as simple as saying you’ll do the right thing and patting yourself on the back for it. It is possible to push your way through each fight without throwing anyone under the bus, without having to engage in your own magically powered version of the trolley problem, but that doesn’t mean the game will make it easy for you. You’ll run into battles where you can try again and again with different strategies, different loadouts, different individual movements. You might end up approaching it like you would Into the Breach, constantly going back a step or two or rebooting the battle entirely, trying to find the “perfect” way to cut through a fight.

But you’ll get frustrated. Worn down and exhausted. Because over and over again, the enemy will cut you down. It’s still not impossible to beat them, but your patience and your optimism get weaker with every fresh attempt.

And then that ability you have, to knowingly throw one of your teammates to the wind so you can turn the whole battle around with ease, going from struggling futilely to cutting soldiers down like wheat, it grows more and more appealing.

The tension and struggle is even better if you play without a guide and go in knowing as little as possible. Sacrificing an ally won’t just affect your story, but it gets back into the game design and its difficulty. If you don’t know what battles are to come yet, you could be shooting yourself in the foot by killing off one of your teammates so you can finally finish one excruciating fight. You don’t know when you’ll get another person to join your party, or if they’re even any good, if their stats and abilities are a good match for what you’re going for and the fights you’ll face. Covenant of the Plume tells a taut story about revenge and the selfishness it can bring out in someone, not by offering you a simple ‘Be a Good Person/Be a Bad Person’ dialogue option at a crucial moment, or by giving you no choice at all and needling you for being immoral, but by using the actual difficulty in a tactics game and the uncertainty of what could happen yet to make it an honest to god struggle about whether or not to take someone else’s life into your own hands.

Doing the right thing isn’t necessarily easy, but doing the wrong thing can just as quickly shoot yourself in the foot too. It’s an incredible demonstration of how game balance can be just as big a part of narrative design as anything else.

6. Fatal Frame II: Crimson Butterfly

There’s this satisfying click to the way Fatal Frame II’s design comes together. Whether it was intentional or not, I cannot say, but the act of playing it gives me this feeling of being a ghost myself. This out of body experience, looking at the world, looking at myself, looking at myself looking at others. It’s all in the cameras, plural. The first-person camera, the locked third-person cameras, and the spirit camera itself that brings you into first-person mode, where you can see everything around you from the eyes of its twin sister protagonists.

I’ve long been a defender of locked cameras, especially in horror games. Getting Resident Evil for PS1 at a way too young age solidified that, even if playing it the first time had me putting the game away for over a month because it just scared me too bad back then. There is camera design in games that makes for much easier, much more intuitive gameplay, but the locked camera opens up grand possibilities for a game designer. To set scenes, to build tension, to intentionally limit what the player can see and how they see it.

I love the way the scenes are set and the cameras are laid out in Fatal Frame II. There’s this beautiful haunting atmosphere and tension from the very beginning as you wander through the woods alone, and it carries through the rest of the game. Fittingly for a game centered around photography, there’s fantastic use of composition everywhere you go, changing up angles to bring shots that stick with you long after you’re done playing. Wandering through the abandoned homes and feeling on edge as you watch the shadows shift and turn with your movements, wondering if you’re being followed, only to see it’s because of the light of a lantern casting through paper walls, or the moon beaming through trees and making the branches loom menacingly, overwhelming you and your shadow, absorbing the both of you into its own shade. There might not be a killer hiding around the other side, but the Fatal Frame series makes the trees themselves menacing. And there’s the nervousness of looking through that same world through the lens of the spirit camera, turning and moving around, never knowing if there might be a spirit just out of your line of sight waiting to cut you down. Limiting your vision, through the locked third-person camera and the boxed in first-person view of the spirit camera, do just as much to menace you as what the game makes you see.

But there’s an aspect unique to 2, not in Fatal Frame 1 or 3, that gave me that ghostly experience, that out of body experience. It’s the fact that twin sisters are the protagonists. From the locked camera view, I am the audience, watching these two slowly move through a haunted world. From the first-person view when I raise that camera up, the fact that I am a participant and not just the audience becomes more stark, more obvious, looking at the eerie woods and village through the eyes of Mio and Mayu Amakura.

And when I turn that camera to look at Mio--or Mayu’s--twin sister, Fatal Frame II completes that ghostly, out of body feeling. I am watching myself, looking at myself. And I can take a photo of myself, to commit to memory. It’s different than looking in a mirror, because the ways you can look at yourself in a mirror are so limited. Whereas Fatal Frame II has spent so much time before you even get the camera to let you see these sisters that you control, that you possess like a spirit yourself, from that distance of the locked camera.

The spirits and the haunts in the game are very well done. But it’s those layers of cameras, of viewing and controlling, of existing and witnessing yourself existing from both a distance and through your ‘own’ eyes, that’s what will stick with me the most.

Cameras can do so much more than take photos. They can disorient and distance you from yourself too, if you’re not careful.

As you’ll find out immediately next, and further down, I ended up thinking a lot about cameras this year.

5. Cellular Harvest

Cellular Harvest is a relaxing, chill photography game of exploratory wonder. The world is soft and gentle. The mood is soothing. It calls to mind a lot of what people most enjoyed about the early editions of No Man’s Sky; jumping from world to world, cataloging it, taking photos, breathing in the wonder of the universe. A relaxing experience of existing and documenting what’s around you, and there being so much around you, so much to see. So much to mine. So much to mark for your interests. So calming, beautiful, wonderful. A galactic collection of postcards, showing all the interplanetary travel you’ve done.

Cellular Harvest brings up all those same feelings to show the casual cruelty that can be hidden inside of them.

With every new year we have more and more games, more stories in general, going “Hey, capitalism is incredibly fucked up? And I hate it?” It’s no surprise, given much of my generation has been living through multiple ‘once in a lifetime’ recessions that we’ve never truly recovered from, alongside an onslaught of other miseries, big and small, too many for me to catalog here. We can just nod our heads at each other and go, “Yeah, I know what you mean”, because we do. So a lot of these games have explored this aspect of capitalism from the aspect of the victims, and the kinds of victims of we are most personally familiar with, because hey, write what you know and all that. Cart Life, Night in the Woods, Kentucky Route Zero, you get the picture.

Cellular Harvest does not take this angle, even while the creators of the game obviously find their solidarity in line with those others tackling the same subject. Instead, it points its eyes, its camera, at the tools of capitalism. The machinery and system of it, the gears that turn within it, how the exploitation happens from the top down, and where the individual comes into play with it, participating it, perpetuating it.

Where does your relaxation come from? How did you get those beautiful sights? What did the people take from those places? What are people trying to sell you? What are the people behind that ‘relaxation’ doing when you’re not looking?

Why are you taking photos of everything? For what end? For who? For what profit?

What is the cost of your relaxation?

It’s not a spoiler to say the premise of Cellular Harvest is that you are an ‘Auditor’, and you have an AI equipped into your suit that calculates the value of everything you photograph in the universe for your corporate bosses. This is not a twist revealed to you at the end of the game to make you go “Hahaha, you were the bad guy the whole time! Is that shocking or what?!” This is the writeup the game has of itself, letting you know before you even boot it up why you’re taking photos, and the reasons you’re doing so are morally vacuous. I think this is important--preferable, really. Going in knowing what you’re doing is wrong, from start to finish. Not admonishing you at the end to twist a knife. Letting it be like it so often is in our life to begin with.

Cellular Harvest gives you an easygoing, relaxing time, because such things are crucial to the way the banality of evil works. It’s very, very easy to go somewhere beautiful, wonderful, and to know it’s being exploited, and that you are part of that exploitation, and to shrug your shoulders and say, “Well, what’re you gonna do?”

So you enjoy the memories you made and the photos you took, even as you passively, quietly know when you look at them that all that beauty is being exploited and mined. For your pleasure and relaxation, or for others. You take a picture, because it really will last longer--capitalism is making sure of it. The phrase becomes a threat and a promise, and you as a gear perpetuating it.

It’s important to remember that your relaxation can--and does--so often come at the cost of others. In No Man’s Sky, while you’re going to each planet and drinking in the sights, you’re also tearing out every natural resource you can for your own use. In Cellular Harvest, you’re enjoying the visual and audio pleasures of your job, knowing that you’re part of the machine making sure this beautiful place won’t stay beautiful, won’t stay untouched.

And in our own lives, the places we look at through postcards and travel catalogs are all the same. Our admiration of the photos has suffering and exploitation, not just outside the framing of the photo, but in the camera itself that took it, and the hand that pressed the shutter button, and the people who paid the person to take those photos.

Relaxation is not neutral, and neither are cameras.

4. Treachery in Beatdown City

I’ve already written thousands of words about the combat system to Treachery In Beatdown City. You can read them over here at Uppercut Crit (and IMO, you should read a bunch of their other stuff too). I’ll give you the short version here: Treachery In Beatdown City doesn’t just love the beat-‘em-ups of the past, it has studied and dissected them for hours upon hours, all so it could see what worked, what didn’t, what needed to be changed, then reassembled it all into one of the most incredibly finetuned combat systems I’ve ever experienced in a game, with a rhythm to the action that feels like breathing. I can’t recommend it enough. Play it, whip some ass, fight somebody.

3. Haunted Cities Volume 4

There are four stories in Kitty Horrorshow’s latest collection of experimental games. They’re all excellent. They’re all tense, they all grab at horror and shape it in ways that form this kind of atmospheric pressure on your skull. Slowly increasing, painfully so, but taking enough time with that pain to let you endure it, get used to it, to feel like it’s a kind of inevitable fact of existence. “What’re you going to do about it, huh?” Instead of worrying about a killer hiding in the dark, it’s fear and pain that climbs on your back in bits and pieces. Building upwards, this invisible tower of uncertainty and worry that you can never quite shake off, but never quite crushes you either. There’s no relief of something simply being ‘over’, of opening the door and seeing that a monster is there--or isn’t. You just keep walking and you get more tired and worn down and the invisible tower never gets any easier to carry. But it never gets so heavy that you can stop, either. The horror has this Sisyphean feel to the atmosphere around it.

All four give me the kind of feelings that I can rattle off about like that, but there’s one in specific I want to go into a little extra detail here. I don’t want to spoil it, really, but I’ll try to get across this piece in it that means so much to me.

The most important moment in “Exclusion Zone” involves an apology. It is given to someone you do not see, will never meet, will never get to talk to. It is a heartfelt apology, one not given for the person delivering it, but for the world simply being so unfair. For being sorry that everyone tried their hardest and wanted to help and they cared but things just didn’t work out because sometimes wanting to do good isn’t enough. Being sorry for the hurt this stranger had to suffer that nobody could do anything about, no matter how hard they tried.

You read this apology while the noises of a Geiger counter are at maximum, knowing you’re being bombarded with radiation the whole time. You see this pain, this hurt, this apology that they suffered so much for no reason, while you too have pain welling up inside of you, the kind also out of your control.

There is pain, and fear, and like Sisyphus, so much of it is out of our control. It hurts, and we cry about it, but even while that pain throbs inside of us, we can reach out and squeeze another person tight, sorry that the word is so unkind to both of us. The pain doesn’t go away, but at least we’re not alone in it, and we know--and we tell each other--we didn’t do anything to deserve it.

Solidarity and kindness as two people enduring forever rolling a hill up a boulder, a bird pecking at our organs.

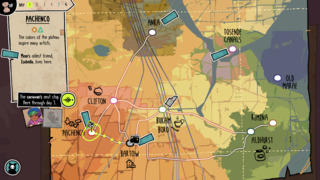

2. Signs of the Sojourner

An easy mistake to make with Signs of the Sojourner, and one I initially made myself, is going into it with the thought of ‘winning’ conversations.

To give context: Signs of the Sojourner is a narrative deckbuilding game. The cards you play are used to navigate conversations, with you matching symbols so you can complete part of a conversation. Do this enough times, and you can finish the conversation on a supposedly positive note. If you and another person are unable to match symbols, then your conversation gets derailed. Take too many hits, and the conversation fails entirely, ending things on a sour note.

Supposedly.

The basic story is thus: You are taking over the caravan work of your late mother, traveling around your patch of the world from city to city, picking up all sorts of things along the way so you can resell them back at the store at home that your mother also left behind. You need to make sure you can get enough items to sell so the caravan still has a reason to come back through your town at all, as it functions as a precious lifeline to not just your store, but the livelihoods of everyone in town. The leader of the caravan is stern, but sympathetic to your own needs--but she’s facing pressures of her own from others to cut your town out for the whole matter of cost/profit ratios of the people far above her. Everyone’s feeling some form of pressure to perform, not just you.

So, as you go from town to town, you have to make conversations with locals, build up relationships, ones of both personal and business needs, so everything can keep running smoothly and your entire life doesn’t get thrown wildly off-track. With how everything is set up, it’s natural to want to ‘win’ every conversation you come across. The instinct is that if you literally and figuratively play your cards right, the world will fall into your favor. And simply on an emotional level, it’s frustrating when you can’t make yourself understood, or understand others, especially those who are personally close and important to you. To not be able to understand or be understood by someone you’ve known your whole life has a particularly rough sting to it.

But you can’t ‘win’ every conversation in real life, and what’s more, you shouldn’t, either. Just as much as you’re playing the game of bartering and haggling, you are being played too. You could have a very positive conversation with someone that ends well, that ends with you and them understanding one another… only to realize that they were keeping your attention on their mouth so you wouldn’t notice when they picked your pocket. Or another person, bragging about their wares with the swaying uncertainty of a car salesman who has been in the sun for 12 hours, aggressively selling their own bullshit but increasingly unable to sound convinced of it. You could have that conversation go ‘positively’… and most likely end up being scammed. Sometimes in negotiation, the best thing you can do is shut things down completely.

Signs of the Sojourner beautifully explores the rhythm of relationships, showing how they’re not a game, even as they’re in a game themselves. You cannot make friends with everyone in the world, nor should you. You can’t have every conversation go swimmingly, nor should you. And when it comes to your limited time on Earth? You can’t experience every single thing you could do, could be. You can’t be everything to everyone, not even to yourself. Your development is a factor of both your circumstances and your own choices. What do you want out of life? How do you want to go about getting it? Who do you trust, and who do you look at with skepticism? Who do you give second chances, and who do you shut out completely? For that matter, who in the world gives you a second chance, and who will never talk to you again after a bad first impression? Some things are in your control and some things aren’t, and how you act and react very clearly shapes yourself, your life, what kind of personal community you build. Even the aches of the body itself play into this; traveling on the caravan takes a toil on your energy, and occasionally puts a card in your deck that will immediately fail a chunk of your conversation, and sometimes your hand will give you no choice but to fail. Speaking clearly and eloquently is hard as hell when you haven’t gotten any sleep or you’ve been working for twelve days straight.

Like I said, it gets the rhythm of conversations, of life. The flow of it all. Choices and consequences build up over time, as do relationships. A conversation can start wonderfully and end in disaster, or go tense and rough but end up with relieving catharsis. Who you are and how you relate to people is not etched in stone, permanent. Nor is it binary, like flicking a switch. It’s a pathway that gets defined the more you tread it, wear grooves into it, but there’s always room for something in the road to take you off guard, even if you’ve been traveling a route for decades.

The conversations are dealt with cards, but the rhythm of it all is far more like the caravan you travel in. What life you end up taking, who you end up being to yourself and to others is not a point A to point B journey, but traveling many roads several times over, and that definition of the self emerging as you go.

One of the best of 2020. Can’t recommend it enough.

1. Umurangi Generation

You’ll likely hear a lot of this sentiment around Umurangi Generation: It’s not just the game of 2020, it’s the game about 2020. And I am no exception.

It’s true on both counts. Nothing else I’ve played has captured this year so well while living inside of it, and the years that had been building up to it. The final mission of the Macro DLC (which I’d also say is the best, most crucial DLC in a game I’ve ever experienced) comes down like a hammer to the chest, vibrating through you about everything in this year, what caused it, what keeps it going, the people its already been happening to for years while the rest of the world ignored it, the cruelty and brutality of it all, and it does it all without a character saying a single word. Completely incredible. It’s the end of the year and I still can’t quite put all my thoughts together on it. It feels like a long term project, a necessary one, to talk about Umurangi Generation’s final stage, to keep it in your memory so you can keep in mind everything that it connects to, a magnetic stone that pulls everything into itself.

Umurangi Generation is a first-person photography game set in the “shitty future” of Tauranga Aotearoa. People have compared it some, stylistically and mechanically, to Jet Set Radio and Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater, just applied to taking photos. It’s easy to see why, with the 3D character models and occasional neon retro-future vibes, combined with the photo bounties you have to complete to finish a level, with bonus bounties to unlock extra photo equipment and filtering tools. Between the art style and the level objectives that might feel to others like “What if you had to photograph S K A T E letters instead of collecting them”, it can be a bit of an instinctive comparison. Especially with the ticking timer, giving you only 10 minutes to complete every objective if you want those bonus unlocks. The mission won’t fail if you don’t get it done in that time. You can take all the time you need to finish off each main bounty. But it definitely adds a little stress, reminding one of the time limit in Tony Hawk to rack up those score goals, find the hidden tape, and so on.

But that’s not what Umurangi Generation feels like to me. It is about so much, and that includes photography. It is not just a shift from rollerblades and skateboards to cameras, it’s about cameras. What they’re for, why one uses them, the work of photography, the liberation of photography, the oppression of photography.

I talked about it in regards to Cellular Harvest, and Umurangi Generation takes it much farther.

“What’s the purpose of a camera?” is something the game asks you, though not directly. It’s more a thought that itches at the back of your head as you play, and at various points, forces that thought to the very front of your mind because the things you’re taking photos of are too intense to ignore the implications of them. To finish a photo bounty of three soldiers smoking cigarettes, you might think nothing of it. To complete your bounties while one of those soldiers is bleeding out right next to you, that’s much harder to pretend it doesn’t mean a thing. And that to take a photo of them means nothing, that how you frame it means nothing. That there’s no ‘why’ to it, and that it doesn’t matter for who or for what purpose you’re taking a photo of them.

A camera is not a neutral object, and taking a photo is not a neutral act. Photography is not a neutral art, and this is one of the most important ways in which Umurangi Generation is about 2020. One of the big ongoing blowups you’d see with news photographers over this year is confusion and indignant anger when people told them not to take pictures of protesters' faces, or to blur them out, something, anything, to make the protesters hard to identify. There was this attitude of “How dare you?!” to so many reacting to these requests, photographers seeing what they did as natural and unobjectionable as water flowing through a creek. They’re there to document history, of course they have to photograph the people, they might say. Sure, the police might, could, would, did use those photos to identify and track down protesters, but that’s not something they, the photographer, should have to think about. So many words spit and written out about their own assumed neutrality, like they were a ghost observing the world, and relaying their photos to other ghosts, who could and would have no impact on what they saw, they would just observe. Seeing themselves as more or less The Watchers from Marvel comics, this egotistical sense that they simply observed history in the making, never affecting it, simply documenting it, and that that documentation is absolutely crucial.

But the photographs aren’t neutral. The news stories they’re used for aren’t neutral. The cropping of the photos aren’t neutral, the color grading of the photos aren’t neutral, the choice of what to focus on and what to leave unseen is not neutral, the choice of which photos a story will opt to include and which they’ll leave out is not neutral, and the cops poring through those photos trying to find some lives to ruin sure as fuck aren’t neutral.

There’s a photograph by Evy Mages, one taken almost exactly four years ago, of a couple dozen people all crowding around a single overturned trash can with a fire in it. It was in Washington, D.C., and it was during the inauguration. It’s comical. All these journalists and photographers looking for something they can sell as “Look at how destructive these protests, these protesters, are!” and becoming obsessed with property damage on the scale of a single trash can fire, crowding around it like they were witnessing the Bastille being stormed. Meanwhile, your local sports team might win--or lose, it really doesn’t matter--a game, and cars might get flipped and torched, entire streets laid to waste, and the mood of the reporting on it, if there’s any at all, is likely to be “Hahaha, boys night! Dudes rock.”

What are you taking photos of? Who for? How are you framing those photos? Why are you taking those photos? What aren’t you taking photos of? What are you INSISTING on taking photos of? It all matters. There’s no neutrality in it, no matter how badly so many photographers want to use their camera as a moral shield, an escape from responsibility of their profession, their art, their existence as a human being. We are not unbiased viewers, giving unbiased coverage and documentation of the world around us and history as it is being made. We are people who affect that world around us, and we cannot pretend we are not because we are choosing to take a photo of a protest instead of marching in that protest ourselves.

I got big into amateur photography over the last couple years, taking photos around my home state of Maine with my phone. I like taking photos of empty spaces the most, in town or in nature, and messing with the lighting and exposure and all to get moody, elegiac photos. So much so that I titled my first photo pack “A Place Without Bodies”, as I was intentionally avoiding, wherever possible, having any physical people in those photos.

And Umurangi Generation has a lot of appeal to the sensibilities I’ve built there. Even with the limits and specifications of bounties, the game let me take photos the way I wanted to. Leaning into the aesthetics and design that most called out to my interests, to the way I liked to look at the world and record it. One thing I say for people playing Umurangi Generation is to, bit by bit, let yourself relax about the bounties. Take your time with levels. Take photos, and figure out for yourself what kind of photos you like to take, what things you like taking photos of, what feels and looks good to you, and why. There is artistic exploration here, and it’s one accomplished without having to hit you on the back of the head telling you all about it. The more you take photos, and the more tools you unlock, the more you think about and tweak “How do I want this photo to look?”, developing your own style. You don’t just snap a photo and finish a job, you can and should take the time as you play to develop your own style of photography. The impulse might be to go for the Perfect, Iconic Shot, something the postcard bounties could fulfill for you, but I say the way to go is to lean back and find what feels right for you, not what you think would necessarily impress others, or ‘should’ go on the cover of a magazine.

Now, I’m not a photojournalist. The photos I take IRL are all on that artistic focus. But that doesn’t mean I, and the camera I use, are neutral either. What I choose to take photos of, or not take, and the same goes for the photos I share, has meaning, impact, weight. Whether I like it or not. Neither I nor anyone else can simply reap the positive aspects of photography and ignore whichever parts make us uncomfortable. The same goes for art of any kind. So of course it applies to photography.

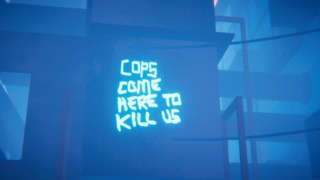

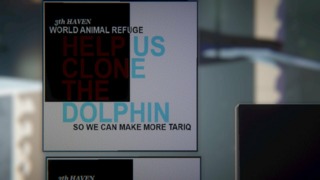

I’ve written all this, and yet, this is just a small slice of what Umurangi Generation is about. What it does. I haven’t said a thing about the fantastic soundtrack, or the dolphin hooked up to a digital vocalizer and turntable equipment and makes music as DJ Tariq. Or talked about how the environmental storytelling in Umurangi Generation is the absolute best I’ve ever witnessed in a game, and the story, the stories it’s telling are breathtaking and span so much ground of humanity. There’s so, so, so much to talk about, all for a game with zero dialog. It’s incredible, beautiful, wonderful, and it is aggressive and I say that wholly positively. It’s easy to associate all those compliments with something serene and tranquil, and while you’ll come across those moments in Umurangi Generation too, it applies just as much to when the game is showing anger, venom, piss and vinegar at the cruelty of oppressive systems and the people who uphold it. All those compliments apply just as much to crude graffiti telling another tagger to shut the fuck up when asked “Have you tried talking it out?”

Game of the year, game about the year, absolutely necessary. Play Umurangi Generation.